Avel de Knight (1923-1995) was an African-American artist, art educator, and art critic. His works are in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Walker Art Center, and the University of Richmond Museums.

De Knight was born in New York. His birth year has been given as 1921, 1923, 1925, 1931, and 1933. His parents immigrated to the United States from Barbados and Puerto Rico. He is the younger brother of René DeKnight.

De Knight studied art at the Pratt Institute from 1941-1942. He joined the Army and served in a segregated unit until the end of World War II. In 1946, he moved to Paris where he used the G.I. Bill to attend the École des Beaux-Arts, Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and the Académie Julian.

De Knight painted watercolors and often practiced the gouache painting technique. He taught at the Art Students League of New York and the National Academy School of Fine Arts.

Visual artist and art professor Stephen J. Tyson, cousin of Avel de Knight and curator of his estate, shared the following in a conversation on the Style Free Podcast on April 9, 2022, the 99th anniversary of de Knight’s birth.

One of the things you find in Avel’s work is the influence of people like Gustave Moreau, the late nineteenth century French symbolist painter who [like de Knight] worked with pastels. Avel was [also] inspired by the life of the mind, of the imagination. He became friends with the writer Jean Cocteau who was also very close friends with Picasso. So being in this milieu of artists who were traversing boundaries – not staying confined conceptually, visually – I think that this spirit of freedom is something that Avel embraced and then exuded through his work; not right away [but] the seeds were sown in France [in the 1940s] and they would later manifest in the mid to late 1960s in his work.

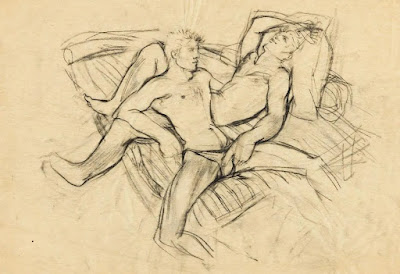

The erotic drawings featured in this post were created by de Knight in the 1940s. Most are from the estate of his close friend, the French artist Julien Outin (1923-2005).

Very little has been written or discussed about de Knight’s personal life and the ways in which his sexuality informed and influenced his art. This is a great pity as it would add much to our appreciation and understanding of his artistic legacy.

Notes the University of Richmond Museums:

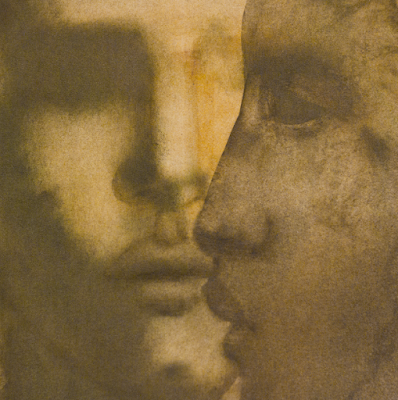

De Knight’s mostly figurative art has been called poetic, lyrical, and symbolist in style. Dream imagery reappears as frequently as classical and African art references. His veils of colors, created by various media, suggest movement, atmosphere, and emotion in these history-laden works.

Above: “Sacred Stones” (1994), pastel on paper, 39.75 x 29 in.

Wrote de Knight: “My ‘mirage’ paintings incorporate within the spatial confines of their ever-receding horizons symbols of personal imagery in which the human element plays the dominant role. . . . The emerging painting magically coalesces and breathes a life of its own.”

Above: Untitled (c. 1974), pen and ink wash on paper, 9½ × 10½ in.

Writes Stephen J. Tyson:

If we want to have an understanding of [de Knight’s] work, we must allow silence to be an acknowledged part of our exploratory journey. De Knight’s work invites us to take this step. It seems to ask us if we are willing to go beyond viewing his skillful technique as an end in itself. Are we willing to see it as a vehicle through which the artist shapes his silence? As we continue to explore the artist’s work, we begin to see an outward continuity of common features: the contemplative figures, deserts, angels, radiant lights, plants, seascapes, shells, masks, and pyramids.

. . . The pyramid, in addition to being a marvel of technical skill in engineering, was designed to house deceased royalty. This particular structure of African antiquity would later become a recurring image in [de Knight’s] Mirage Series. He regarded the mirage experience as involving the advancement toward an unreachable or unattainable goal or ideal. The pyramid itself represents an ideal. With this form, together with the reduction of human presence and the atmosphere of mystery, he appears to be grappling with the themes of death and eternal life. They would become more explicit in his work toward the end of his life.

Related Off-site Links:

• Avel de Knight

• Avel de Knight: American Artist

• Visions Beyond: The Artistic Legacy of Avel de Knight

• Avel de Knight’s Myths and Mirages

• Oral History Interview With Avel De Knight, July 22, 1968

• The Avel de Knight Facebook Page

• Who Is Avel de Knight?

• A Conversation About the Artist Avel de Knight

See also: The Art of Frank-Joseph Frelier | Claudio Bravo | John Singer Sargent | Salem Beiruti | Ismael Álvarez | Stefano Junior | Alireza Shojaian | Frédéric Bazille | Saul Lyons | Barkley L. Hendricks | Alexis Vera | Mauna Nada | Ego Rodriguez | Liam Campbell | Richard Vyse | David Jester | Aaron Moth | Travis Chantar | Douglas Simonson | Guglielmo Plüschow | Vilela Valentin | Dante Cirquero | Nebojsa Zdravkovic | Brenden Sanborn | Wilhelm von Gloeden | Richard Haines | John MacConnell | Leo Rydell Jost | Jim Ferringer | Juliusz Lewandowski | Felix d'Eon | Herbert List | Joe Ziolkowski